Actually, a Fourth of July picnic in the park with family, friends and neighbors presents the perfect scenario to think about all the ways we use chemical potential energy without even thinking about it. On a deeper level, the bonds we chemically make or break—and maybe make again—are reflected in the bonds we create or destroy with other people, locally and nationally.…

jamie zvirzdin

Citizen Science No. 17 by Jamie Zvirzdin Energy Demystified: Bounce Back This Summer with Elastic Potential Energy What do ballpoint pens, Slinkies, your muscles and tendons, and my dog’s running leash have in common? Last month we talked about potential energy (PE for short). It’s a beautiful, invisible physics quantity that stores energy based on where something is placed, like a book on a high shelf. The book now has the potential to fall, but it hasn’t fallen yet. While…

Iron String Press is the sole remaining independent and locally owned newspaper publishing enterprise in Otsego County. Through its print publications and its digital counterpart, AllOtsego.com, Otsego County households have the benefit of local news in local hands at a time when the U.S. is losing an average of more than two community newspapers each week.…

Potential energy is the energy stored in an object because of its position, condition or state. It’s the energy of anticipation, the calm before the storm, the coil in the spring, the water held back by the dam, the double-A battery fresh from the factory, the caterpillar before the butterfly, that butterfly and all his friends and relatives in your stomach right before the roller coaster’s plunge.…

As a pioneering philosopher-mathematician in France, Émilie Du Châtelet argued, as Leibniz did, that a fundamental quantity of motion existed beyond the idea of momentum, which she called the force morte, “the dead force”...…

I find a great deal of value in contemplating both the physical and metaphysical—dare I say spiritual—forms of work, so we’ll have fun blending them here.…

This year, join me as we bridge the gap between understanding energy in the scientific sense and harnessing it in our daily lives. As we increase our knowledge of energy, we can also adopt practical, tried-and-true methods to boost our own energy levels...…

Filtering water closely parallels the filtration of our daily information intake. It takes time and effort. Full filtration is particularly expensive, costing a great deal of time and effort; however, the cost may be less severe with cleaner sources.…

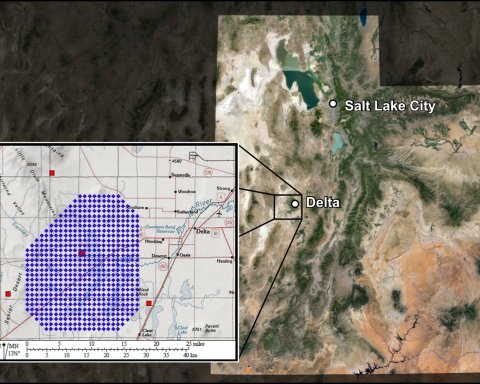

Last week, Thanksgiving 2023, the Telescope Array Collaboration announced the detection of a UHECR named Amaterasu (https://scienmag.com/telescope-array-detects-second-highest-energy-cosmic-ray-ever/)…

When we’re young, the world unfolds in found talismans and nursery ditties. Singsong superstitions are verses in the narratives we construct about our lives. I was no exception. Sidewalks transformed into mythical landscapes, each crack a fault line through which my mother’s well-being might crumble.…